Â

[In questo post: Soliloquy]

Non so se sia effettivamente definibile “postmoderno”. Sicuramente è un esperimento singolare, e in barba a tutti quelli che dicono: bè, che ci vuole, potevo farlo anche io. Oh sì, potevi farlo anche tu. Ma non ti è mai venuto in mente, perciò apprezza lo sforzo e non cercare di passare per il creativo di turno perché è chiaro che non lo sei. No, a parte gli scherzi. Il signor Kenneth Goldsmith deve aver letto Joyce o comunque averne sentito parlare un bel po’ per farsi venire in mente un’idea del genere: prendi un registratore, infilaci una cassetta (siamo nel 1997), premi la magica combinazione di tasti REC+Play e appendi il tutto al collo. Non separartene per una settimana. Lascia che ogni tua parola si stampi sul nastro. Qualsiasi cosa tu dica, qualsiasi, senza censure. L’altra regola del gioco è che solo le tue sillabe hanno il diritto di essere registrate.

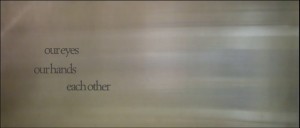

L’eco dell’ Ulisse si sente forte e chiara: come Joyce segue Leopold Bloom da mattina a sera per circa 600 pagine di quasi ininterrotto flusso di coscienza, allo stesso modo il nastro del registratore è il torrente di parole che Goldsmith pronuncia in una settimana. Niente di più naturale, ovvio e scontato, direbbe il nostro amico di cui sopra. E invece non c’è niente di più artificiale che sentire dei dialoghi mozzati in cui solo una voce è udibile, un romanzo in cui autore, narratore e protagonista non potrebbero coincidere meglio, un soliloquio (come il titolo stesso del lavoro di Goldsmith) in cui ogni frase ci viene data sempre fuori contesto. Per giunta, come spiega in un saggio semplice e brillante Marjorie Perloff, “non abbiamo accesso ai pensieri nascosti del narratore, ai suoi movimenti fisici . . . ai suoi sogni ad occhi aperti . . . questo è come sarebbe la vita se gli uomini non potessero fare altro che parlare” [mia traduzione].

Qualche giorno fa ero ad una lezione di critica e teoria letteraria tenuta dal prof. Aciman, un grande scrittore oltre che un grande uomo di cultura. Insomma, parlavamo di Castiglione e di “sprezzatura”, cioè del fatto che la classe e l’apparente eleganza dei gesti spesso non sia così naturale, ma richieda una certa cura, un’attenzione e un’abilità a non sembrare affettati e costruiti negli atteggiamenti e nel modo di porsi. Lo stile, in sostanza, richiede fatica per sembrare naturalmente così. L’esempio lampante è Twitter: solo 140 caratteri, che ci vuole? Bè, una regola tanto semplice può causare serie difficoltà . Esprimi un pensiero in 140 caratteri. Finché si tratta di dire “voglia di studiare saltami addosso, dimmi quando salti che mi sposto” (70 caratteri) o “Stamattina stavo per investire uno scoiattolo, ho dovuto inchiodare in mezzo alla strada a momenti ci lasciavo la pelle, sto cretino” (132 caratteri), allora 140 vanno più che bene. Ma cosa succede se volessi scrivere, che ne so, il riassunto di un film che ho visto in così poche parole? O la recensione di un libro? Si fa, ovviamente. Questione di stile.

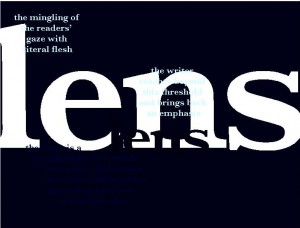

Ma tornando al nostro caro Kenneth: originariamente il suo Soliloquy era un’istallazione museale. Dopo 8 settimane di ritiro nella campagna francese, lavorando otto ore al giorno, trascrisse parola per parola tutto quello che aveva registrato, stampò il tutto e i 314 fogli risultanti furono appesi fino a coprire interamente le pareti di una sala della Bravin Post Lee Gallery di New York.

Successivamente ne è stato fatto anche un libro – non m’immagino comunque abbia riscosso un grande successo, e da ultimo è arrivata la versione web. È strutturata secondo 7 capitoli, uno per ogni giorno della settimana. Ogni capitolo ha poi 10 microsezioni al suo interno, in cui al passaggio del mouse compaiono le frasi pronunciate da Goldsmith. Solo la prima è stabile sulla pagina, le altre vanno fatte emergere una dietro l’altra. Se si ha pazienza e mano ferma per seguire una sorta di linea retta, è possibile seguire il filo del discorso, altrimenti (e il bello è questo secondo me) si può semplicemente vagare per la pagina e curiosare qua e là .

Buona lettura!

Â