Â

[In this post: Lens - please select it from the left column of the linked page, there's no way of directly linking it]

“The surface of writing is and has always been complex. It is a liminal symbolically interpenetrated membrane, a fractal coast – a borderline, a chaotic and complex structure with depth and history”.

(John Cayley, “Writing on complex surfaces”, 1)Â

When I first saw Cayley’s article, I was hooked by its title. I thought: “Finally someone who realizes that writing is tri-dimensional, if not multi-. Especially if we talk about electronic literature, it must be so. Just think about all the media that you can embed, all the fonts you can choose, all the colors that backgrounds can have. Texts seem to become alive”.

But then, when I started reading, the name that kept popping out was Saul Bass. Who is Saul Bass? I didn’t know him either, as you are probably thinking. Then I checked his name up in Wikipedia (of course, where else?) and here it is what I’ve found:

“Saul Bass (May 8, 1920 – April 25, 1996) was an American graphic designer and Academy award-winning filmmaker, but he is best known for his design on animated motion picture title sequences.”

So what do a title sequences designer and electronic literature have in common? According to Cayley,  the use Bass made of graphics was one of the first examples of how a writing surface can become complex making letters, numbers and other geometric shapes material and interactive between themselves and with their background.

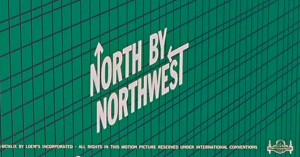

His distinctive feature was the rule, which was used not only to manage the spaces in which words appear, but interfered with the surface of writing and became a surface of writing itself (4). According to Cayley, Bass’s most successful work was the title sequence for Hitchcock’s “North by Northwest”, for its transformation of the green ruled background in a skyscraper’s façade ”in a continuum (italics mine) of retorical possibilities and signifying strategies that cross and recross from graphic to linguistic media and back [. . .] without loosing a grip on their specific materialities” (5).

Â

Â

As the sequence of picture shows, the passage from the initial green background to the final image of glass and steel reflecting the hustle and bustle of a crowded city is absolutely gradual and continuous while words keep moving up and down as they were elevators. Cayley points out that the link with Concrete poetry is almost obvious (5) but he doesn’t insist much on this. Maybe it could have been a good point to show that even when literature could only be printed, it tried to go out from the surface of paper and communicate something not only through the meaning of the words but also through their shapes, fonts and disposition on the sheet. Anyway Mr. Cayley, I do appreciate your original approach to the subject starting from a kind of art, that is graphics, which personally I am not well aware of, but for sure its development in the same years in which Concrete poetry, computers and post-modernist avanguardist movements were spreading is not a chance. It’s part of the innovative and cutting-edge ambience of that years.

Graphics aside, in the second part of his essay Cayley deals with much more literary-specific topics, that is the Screen virtual reality experiment held at the Brown University Cave some years ago (about which you can read more here) and some other works which have been experimented in the Cave but that you can find on the Internet now. The only negative aspect of these latter, well, not negative, but a little bit annoying, is that you need the last version of Quicktime and, in some cases, you have to download a couple of sound files. But anyway, it takes no more than 5 minutes.

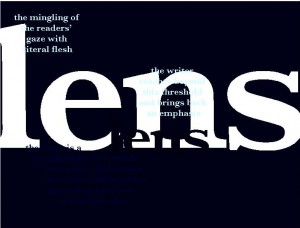

My favorite is absolutely “Lens“, as it perfectly matches the idea of “continuum” in the sense that words through graphics open different layers of text, which otherwise would have been hidden.

My favorite is absolutely “Lens“, as it perfectly matches the idea of “continuum” in the sense that words through graphics open different layers of text, which otherwise would have been hidden.

Cayley focuses mainly on overboard and translation, which are actually examples of texts emerging from and sinking in the page. Translation is conceptually based on Walter Benjamin’s theories on translation, and I believe that it’s a perfect way of rendering the metaphor of translation as a discovery of different meanings and senses from one language to another.

This is exciting. And so intresting too!!!! Only you could have done it B.

CuL8er, C

Lo and Behold who’s there! Thank you Chiara! <3